Many well-meaning people have told me that Mack is an angel now, in Heaven. That she is eating infinite quantities of sour candies, sushi, and Thai fried rice in a place where the weather is ever perfect for her open Jeep to drive down beautiful, tree-lined avenues, music blaring, with a car full of puppies. I do not doubt that religious belief eases the burdens of grief for religious people. Yet I cannot seek comfort in the magical thinking of religion. For me, death is terminal to the flesh and to the soul. I keep the spirit of Mack within me and allow her impact upon my life to guide me, going forward, but my grief is grounded in the painful reality that neither her body nor her soul inhabit any world. And so, in the absence of spiritual solace, I seek a more tangible comfort.

I have spent innumerable hours pondering this idea of angels, of the meaning of the people who pass through our lives and of the trauma their deaths inflict upon the living—the people they leave behind in the world to understand and to make peace with the fragility of being human. Losing Mack ripped open the flesh of my emotional vulnerability and offered shocking clarification of my own mortality and of the mortality of every single person I love and need. But losing Mack also uncovered, in the exposure of my bones, other lost people, living there, with me still, although long gone from the world of the living. In the parlance of the religious observer, I have three angels: Mack, my dad, and my maternal grandmother. But I have come to understand that the bold impression that each of these three marvelous humans made upon me and the tangible guidance they continue to provide me are much more powerful than any otherworldly existence they would inhabit if heaven was a place and angels lived there. But what does any of this babble mean, anyway, and why do I feel compelled to define Mack, Jim, and Kathleen as something other than angels?

There is a historical debate about whether upon Abraham Lincoln’s death, his Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton consigned Lincoln to the “angels” or to the “ages.” If one subscribes to magical thinking—as author Joan Didion argues every grieving person does, at least at the immediate impact of a loss—then it is likely that perhaps all of the people present for Lincoln’s last breath, each of them grounded in Christian theology, believed Lincoln had joined the angels in Heaven. Certainly Mary Lincoln believed it so. But what we have learned in the 153 years since Lincoln’s death is that he actually resides with the living. He does not inhabit some ethereal plane as an angel, but rather he belongs to the ages, regardless of what Stanton might have actually said. Lincoln exists in the bones of America; just as Mack, Jim, and Kathleen exist in my bones. Lincoln is, for Americans, a folk hero—a tangible historical presence who corroborates our past, who by the example of his own leadership offers tools for leadership in the present, and who in his human worth provides inspiration for the future of America. Mack, Jim, and Kathleen are, for me and for my life, folk heroes—the tangible comfort I seek, because they corroborate my past, they by the examples of their own lives give me tools to navigate my life in the present, and in their human worth, and from their significance in my life, inspire me to gaze forward, onward, toward the future.

In looking back across three and a half years of the blog entries in Being Mack’s Momma Bear, I realize that what I have written is a series of “Mack-tales,” stories of Mack’s life and the influence she had upon the people who knew her, many told with some moral or inspirational purpose beyond the story itself. My individual stories about Mack are all true, but taken together, they read as folktales; and Mack, I think, reads like a folk hero. It is not my intention here to argue that Mack is a folk hero in the way that Abraham Lincoln is a folk hero. Rather, my point here is that we all have people we have lost who are so much more than angels looking down upon us from some kind of heaven, happy away from the ones who loved them, looking down upon mere mortals through some bright, heavenly light. And I also think it is good and useful, in fact it is a tangible comfort, to recognize the folk heroes we were so damn lucky to know and to keep them with us by telling their stories. Perhaps not for the ages, but for us and for our immediate families, as a way to make sense of life, of death, of the world around us, and of our fragile but beautiful human connections.

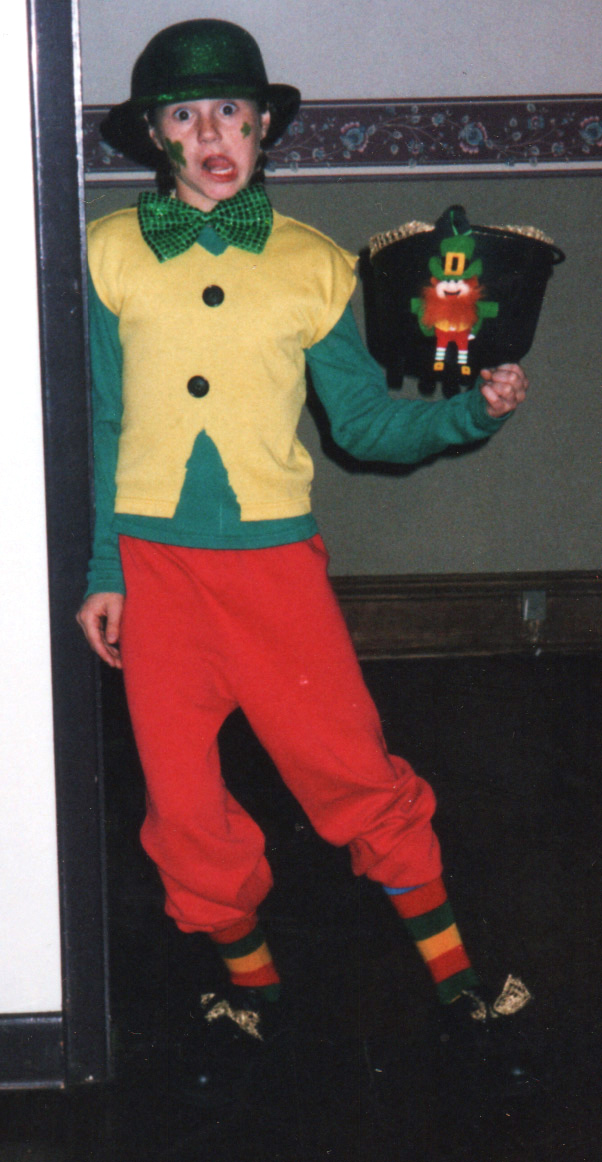

I am going to keep pondering this idea of folk heroes, and probably of angels, too. It is a topic, as yet unresolved in my brain, and about which I intend to write more. But for now I want to tell you about my first folk hero, my grandmother, whose name I gave as a middle name to Mack and whose stories I shared with my girls as they grew. My grandmother died when I was in graduate school, and she was with me, tucked deep within my bones, throughout my doctoral studies as I gutted out soul-crushing seminars, grueling reading lists, and inhuman schedules. My memory of her grit and her sass offered me strength and solidarity from beyond her grave. I did not have any real sense at the time that she was with me or that I had attached so much purpose to my memories of her. But now I do, as it is one of those curious light bulbs that have switched on in my psyche, through the fog of my grief for Mackenzie. So on what would have been her 95th birthday, I give you Kathleen: a woman, a grandmother, a folk hero. See for yourself why she is so deep within my bones and how much of her folk-hero character and traits ended up in the bones of Mack, as well.

Kathleen was a hard-working, tough-talking woman who survived the depression, sacrificed during World War II, and suffered premature widowhood and early breakdown of her body and her health. She was a real-life Rosie-the-Riveter who swooned over Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley. She was a diabetic addicted to sweets and to junk food. She was a house-dress-wearing, pocket-book-carrying granny who enjoyed pinching and teasing her grandchildren and wrapping them up in bone-crushing bear hugs. She had the delicate penmanship of an artist, the mouth of a dishonorably discharged marine, and she crocheted colorful blankets while watching professional wrestling. Kathleen did not bake pies and whisper; she worked in a box factory and told dirty jokes. She was crass and direct and devastatingly funny, full of chutzpah, contradictions, and complexities. She was true to who she was and how she felt and what she thought, and she never apologized for any of it.

Kathleen indulged my sweet tooth, once cheering me on as I devoured a Hostess Ding-Dong in one outrageously large bite. She appreciated and encouraged my spunk. She taught me to use my middle finger with authority, both literally and figuratively, and she showed me how to be bold in the big, bad world. She adopted my friends without putting on fake grandmother airs. She made card games uproariously fun, but she also made them dangerous, threatening to get those who bested her with her “bowling-ball grip” as she gestured over the card table, three angry fingers pointing skyward. First-time hearers of Kathleen’s unique and sometimes obscene vocabulary gaped, veteran hearers tittered, and everyone, in the end, understood that in speaking her truth in her own language, Kathleen had scooped them up into her bosom to love them, to boss them, to be herself with them, and to bear witness to their true selves, as well.

A 1943 photograph of Kathleen is one of three perched within the deep grooves of a giant framed mirror on the floor in my bedroom. In her photo, Kathleen is wearing a vibrant floral dress and is wrapped up in the arms of my handsome, uniformed grandfather who will soon be in Europe fighting Nazis. On the right is a photograph of Jim, my father, in 1981. Standing in my childhood kitchen, he is wearing a suit vest, tie, and an impish grin as he holds up a glass-bottle of Pepsi. In the middle photograph is my precious Mack in 2010. Clad in her red, high school basketball silks, bearing her lucky number 4, she spins a basketball atop her long, right index finger. When I propped up those photographs there, more than three years ago now, I had not given much thought to the intent of their placement. But now their purpose is perfectly clear. These are the photographs of my folk heroes, spanning nearly seventy years of time and history. Mack, Kathleen, and Jim are folk heroes. No different, really, than Abraham Lincoln, Johnny Appleseed, Paul Revere, or any other folk hero you might imagine–at least not to me. My memories and my stories of them are the folktales of my life, and they are my tangible comfort. They root me to my past and to my Indiana ancesters, they ground me in the present guiding me by the examples of the lives they led, and they inspire me to see a future, even if it is one without them.

And, that, my friends, as you likely already know, is precisely what folk heroes are supposed to do.

I cannot now recall the particular details of the assignment, but there were rules about dimensions and weight and solid objects did not qualify. Mack and her dad dug through the scrap wood in the basement, did some measuring and sawing, and came up with a hefty little step (measuring in at 11¾” x 5.5″ x 2¾”) with a big hole in the middle of it. Not satisfied that the bare wood did the successful design justice, Mack personalized it in Irish-green spray paint and some stick-on letters.

I cannot now recall the particular details of the assignment, but there were rules about dimensions and weight and solid objects did not qualify. Mack and her dad dug through the scrap wood in the basement, did some measuring and sawing, and came up with a hefty little step (measuring in at 11¾” x 5.5″ x 2¾”) with a big hole in the middle of it. Not satisfied that the bare wood did the successful design justice, Mack personalized it in Irish-green spray paint and some stick-on letters.